WHO publishes its new International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11)

Coding disease and death

There are few truer snapshots of a country’s wellbeing than its health statistics. While broad economic indicators such as Gross Domestic Product may skew impressions of individual prosperity, data on disease and death reveal how a population is truly faring.

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) is the bedrock for health statistics. It maps the human condition from birth to death: any injury or disease we encounter in life − and anything we might die of − is coded.

Not only that, the ICD also captures factors influencing health, or external causes of mortality and morbidity, providing a holistic look at every aspect of life that can affect health.

These health statistics form the basis for almost every decision made in health care today − understanding what people get sick from, and what eventually kills them, is at the core of mapping disease trends and epidemics, deciding how to programme health services, allocate health care spending, and invest in R&D.

ICD codes can have enormous financial importance, since they are used to determine where best to invest increasingly scant resources. In countries such as the USA, meanwhile, ICD codes are the foundation of health insurance billing, and thus critically tied up with health care finances.

Crucially, in a world of 7.4 billion people speaking nearly 7000 languages, the ICD provides a common vocabulary for recording, reporting and monitoring health problems. Fifty years ago, it would be unlikely that a disease such as schizophrenia would be diagnosed similarly in Japan, Kenya and Brazil. Now, however, if a doctor in another country cannot read a person’s medical records, they will know what the ICD code means.

Without the ICD’s ability to provide standardized, consistent data, each country or region would have its own classifications that would most likely only be relevant where it is used. Standardization is the key that unlocks global health data analysis.

Ready for the 21st century

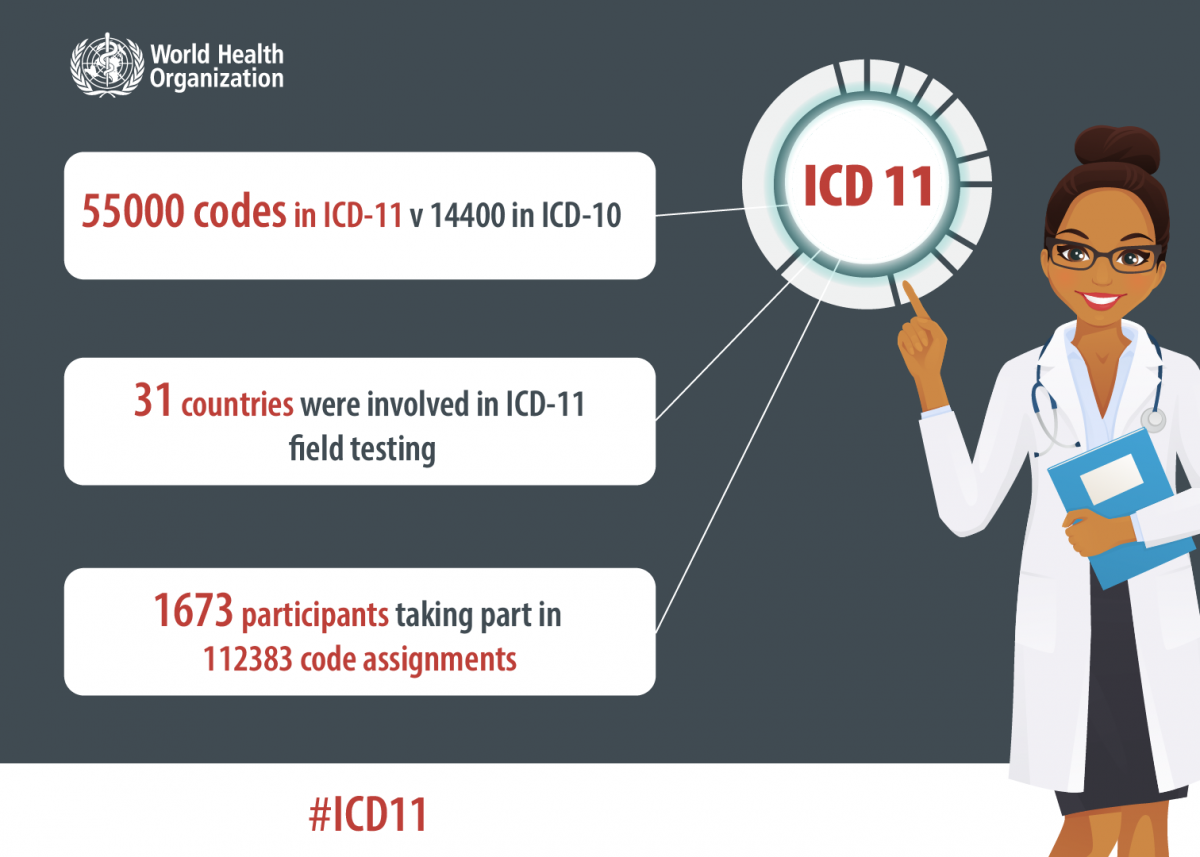

On 18 June 2018, 18 years after the launch of ICD-10, WHO released a version of ICD-11 to allow Member States time to plan implementation. This is anticipating the presentation of ICD-11 to the World Health Assembly in 2019 for adoption by countries. Over a decade in the making, this version is a vast improvement on ICD-10.

First, it has been updated for the 21st century and reflects critical advances in science and medicine. Second, it can now be well integrated with electronic health applications and information systems. This new version is fully electronic, significantly easier to implement which will lead to fewer mistakes, allows more detail to be recorded, all of which will make the tool much more accessible, particularly for low-resource settings.

A third, important feature is that ICD-11 has been produced through a transparent, collaborative manner, the scope of which is unprecedented in its history (see Box: The revision process). The complexity of the ICD has sometimes made it seem like an esoteric health tool requiring months of training – of the number of deaths reported in the world, those coded correctly were about one third. An overriding motive in this revision was to make the ICD easier to use (see Box: Making the switch).

Small code, big impact

The consequences that ICD coding has on provision of care, as well as health financing and insurance, means that clinicians, patient groups, and insurers, among others, take the use of the ICD extremely seriously – many groups often have strong positions on whether or not a condition should be included, or how it should be categoriszed.

The consequences that ICD coding has on provision of care, as well as health financing and insurance, means that clinicians, patient groups, and insurers, among others, take the use of the ICD extremely seriously – many groups often have strong positions on whether or not a condition should be included, or how it should be categoriszed.

For instance, some people working on stroke have long been pushing for it to be moved from circulatory diseases, where it has been for 6 decades, into neurological disease, where it now sits in ICD-11. Those advocating for the move cited key implications for treating the disease and reporting deaths as the main driver.

A critical point in engaging with the ICD is that inclusion or exclusion is not a judgement on the validity of a condition or the efficacy of treatment. Thus, the inclusion for the first time of traditional medicine is a way of recording epidemiological data about disorders described in ancient Chinese medicine, commonly used in China, Japan, Korea, and other parts of the world. Revisions in inclusions of sexual health conditions are sometimes made when medical evidence does not back up cultural assumptions. For instance, ICD-6 published in 1948 classified homosexuality as a mental disorder, under the assumption that this supposed deviation from the norm reflected a personality disorder; homosexuality was later removed from the ICD and other disease classification systems in the 1970s.

Gender incongruence, meanwhile, has also been moved out of mental disorders in the ICD, into sexual health conditions. The rationale being that while evidence is now clear that it is not a mental disorder, and indeed classifying it in this can cause enormous stigma for people who are transgender, there remain significant health care needs that can best be met if the condition is coded under the ICD.

For mental health conditions, ICD codes are especially important since the ICD is a diagnostic tool, and thus, these are the conditions that often garner much of the interest in the ICD. These include gaming disorder, which evidence shows is enough of a health problem that it requires tracking through the ICD. Other addictive behaviours such as hoarding disorder are now included in ICD-11, and conditions such as ‘excessive sexual drive’ has been reclassified as ‘compulsive sexual behaviour disorder’.

A significant change in the mental disorders section of ICD-11 is the attempt of statisticians to simplify the codes as much as possible to allow for coding of mental health conditions by primary health care providers rather than by mental health specialists. This will be a critical move since the world still has a scarcity of mental health specialist – up to 9 out of 10 people needing mental health care don’t receive it.

History of the ICD

The history of the ICD traces back to England in the 16th century. Every week, the London Bills of Mortality would announce deaths from distinctly medieval causes: scurvy, leprosy, and the big killer – plague.

It wasn’t until the late 19th century though, when Florence Nightingale, just returned from the Crimean War, advocated for the need for gathering statistics on causes of disease and death that data began to be collected more systematically.

Around the same time French statistician Jacques Bertillon introduced the Bertillon Classification of Causes of Death, which was adopted by several countries.

In the 1940s, the World Health Organization took over Bertillon’s system and expanded it to include statistics on causes of injury and disease, producing the first version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death (ICD). This allowed for the first time the collection of both morbidity and mortality data to map both disease trends and causes of death.

Disease trends and the biggest killers

The data captured through ICD codes is of huge importance for countries. It allows for the mapping of disease trends and causes of death around the world, which are key indicators both of the health of a population, but also the social determinants that link closely to health, such as the education, nutrition, and public infrastructure - in short, a snapshot of where a country’s vulnerabilities lie.

A country in which people live in crowded, inadequate housing with no clean water are inevitably likely to have a higher incidence of diarrhoeal disease.

The Global Health Observatory is WHO’s gateway to health-related statistics for over 1000 indicators. Data coded through the ICD populates the Global Health Observatory allowing WHO to report World Health Statistics annually.

These statistics are critical in tracking progress towards key targets such as the Sustainable Development Goals.