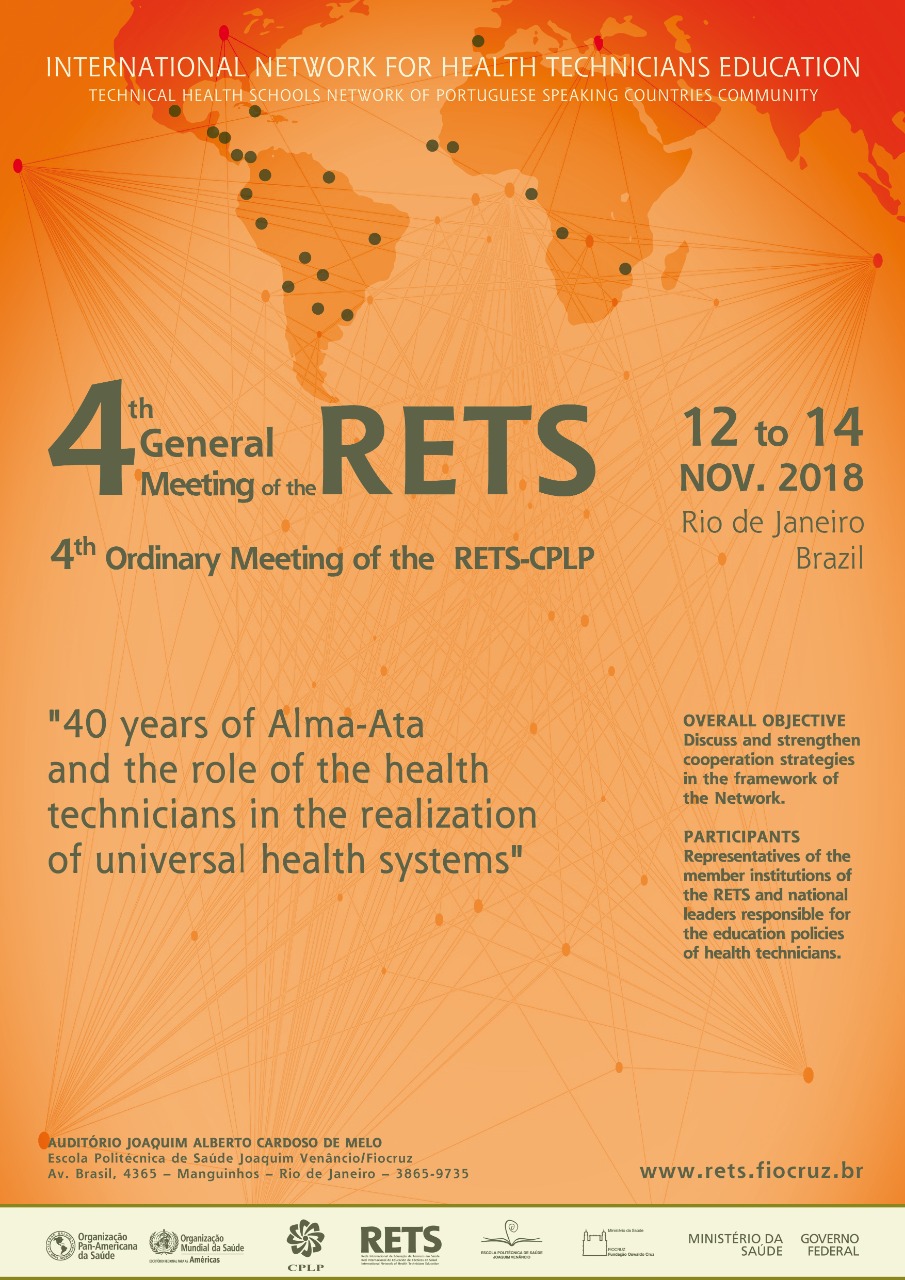

4th General Meeting of the RETS: "40 years of Alma-Ata and the role of the health technicians in the realization of universal health systems"

The 4th General Meeting of the International Network of Health Technicians Education (RETS) will be held from November 12 to 14 in Rio de Janeiro, together with the 4th Regular Meeting of the Network of Technical Health Schools of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (RETS-CPLP). The first part of the program - the seminar '40 years of Alma-Ata and the role of the health technicians in the realization of universal health systems' - will be open to the general public and broadcast live on the Internet in Portuguese and Spanish).

In the seminar, Paulo Buss, the former president and current coordinator of Fiocruz's International Relations Center (CRIS), will present the theme 'From Alma-Ata's declaration to Astana's declaration: universal right or universal health coverage?'. Isabel Duré, from the Department of Health, Ministry of Health and Social Development of Argentina, will discuss 'Unfinished agenda of training and work of health technicians after 40 years of the Alma-Ata Declaration'. The roundtable, which will be moderated by the professor and researcher Márcia Valéria Cardoso Morosini, from the Polytechnic School of Health Joaquim Venâncio (EPSJV/Fiocruz), will take place on November 12 from 9:00 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. (Brasilia time)) in the EPSJV Auditorium.

In the specific scope of the Networks, the event has as objectives:

- To consolidate RETS and its mission to support the strengthening of training and qualification of health technical workers, in international cooperation processes in the Americas and in the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries (CPLP);

- Strengthen the teaching, research and institutional development actions of the institutions that integrate RETS and its sub-networks;

- Prepare working and communication plans for RETS and RETS-CPLP;

- Review the regulations and elect coordinating institutions for the coming years.

The Meeting is being organized by EPJV/Fiocruz, as the Executive Secretariat of RETS, with the support of the representation in Brazil of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/WHO), the International Affairs Office (AISA) of the Ministry of Health of Brazil, and CRIS / Fiocruz.

The Health Workforce: A Concern for Global Health

RETS was created in 1996 in response to the outcome of a large multi-center study on the training of health technicians in the Americas, coordinated by PAHO/WHO. The aim was for the Network to function as a space for the production and diffusion of knowledge that could guide and provide a more solid basis for the elaboration of public policies focused on the training and work of health technicians. RETS is, therefore, part of a set of initiatives aimed at solving a problem that for many years has been central to the discussions on health in the world.

The shortage of the health workforce was the subject of the 2006 Report of the World Health Organization (WHO) - "Working Together for Health" - but long before the problem was already considered a critical point for achieving international goals health and development. The Joint Learning Initiative report, released in 2004, the various resolutions of the World Health Assembly calling for international action to address the crisis, and the "Toronto Call to Action for a Decade of Human Resources in Health (2006 -15)", which sought to mobilize national and international actors, the health sector, other relevant sectors, and civil society to collectively build policies and interventions for the development of human resources in health are some signs of the importance of this theme.

Another notable development was the creation in May 2006 of the Global Health Workforce Alliance (GHWA). The Alliance brought together governments, civil society, international and regional institutions, professional associations, academia, and the private sector to discuss issues related to the health workforce: health, work, management, governance, finance, education, research, data collection, and planning. Its purpose was to lead efforts to address the health workforce crisis, based on the WHO Report. On May 15, 2016, the Alliance ended its 10-year term and transitioned to the Global Health Workforce Network, which operates within WHO, as a global mechanism for multi-sector collaboration and policy dialogue. support the implementation of the "Global Human Resources Strategy on Health: Workforce 2030" and the recommendations of the High-level Commission on Employment in Health and Economic Growth, set up at the UN in March 2006. On the issue of health human resources in the new global agenda, WHO also published the same year, "The requirements of the workforce for universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals". During its ten years of existence, GHWA has organized three Global Forums on Human Resources for Health: in Kampala, Uganda (2008); in Bangkok, Thailand (2011); and in Recife, Brazil (2013). A fourth Forum was held in Dublin, Ireland, in 2017 after the transformation of the Networked Alliance.

In the Region of the Americas, the theme has also been in focus for all this time. In 2017, PAHO defined the"Strategy for Universal Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage", which plan of action was approved in September of the same year.

Despite all the efforts made over the last 20 years, the WHO recognizes that there are still many problems to be solved and highlights the following aspects in general:

- There is a shortage of some categories of health personnel in almost all countries, and in many, there are not enough doctors, midwives, nurses, and aides;

- Workers get older, retire, and there are no consistent plans for their replacement;

- Availability and accessibility continue to vary greatly within the countries themselves because of the difficulty of attracting and retaining staff;

- Adapting content and training strategies is still a major challenge in all countries;

- Few countries have the capacity to calculate the future needs of human resources for health and to design long-term policies;

- Strengthening information systems on the health workforce is critical to better and more efficient decision making; and

- The political commitment of the national authorities was critical in countries that have shown improvements in the health workforce.

The technical workers of the health

One of RETS 'efforts throughout its existence has been the affirmation of the lack of professional recognition and the political invisibility of the category of technical workers in the formulation of governmental policies and actions, including Primary Health Care. Some initiatives, such as projects Mercosur I and II: a joint research conducted by institutions in Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina and Paraguay, which resulted in the publication of two books: "The Silhouette of the Invisible: the Training of Technical Workers in Health in Mercosur" and "The training of technical workers in health in Brazil and in Mercosur" (both in Portuguese). The objective of the research was to broaden the reflections on who they are, what they do and where these workers are assigned. Nevertheless, there remains the difficulty of constructing a regional or even global definition for the term 'technical workers in health', in particular, the historical difference between the countries involved in the educational level where such training takes place (middle or higher).

There are also important differences in the characteristics of institutions that are responsible for the training of technicians at home country: technical schools, public health institutes, university institutions or non-university centers. There are also different types of teaching - face-to-face and distance learning, linked to a general training component or just a specific technical component; broad or restricted workload; whether or not there is an internship - and technical workers who have not previously undergone any initial training for professional practice, known as ancillary or practical.

In addition to these aspects, in each country the insertion of technical workers in health in the world of work is carried out according to the historicity of health, education and work policies, but also with the role of professional corporations and regulatory bodies of the professions. This set of aspects determines, for example, the training, the certification, the definition of the degrees of autonomy with respect to their professional practice and subordination of these workers, as well as the areas and/or subareas of professional qualification, that conform different attributions.

This complex scenario continually reaffirms the very existence of RETS and the necessary expansion of cooperation projects among its members. For this purpose, within the Network, the technical work in health is considered as all that carried out by the group of workers who carry out technical and scientific activities in the sector and comprises from the activities of a simpler nature, carried out by the auxiliaries and community health agents , to those of a more complex nature, performed by technicians of higher level.

The fact is that different degrees of qualification for professionals with similar training or even a same denomination applied to workers with different backgrounds and assignments makes it even more difficult to collect and make available data on these workers, including by international organizations. However, even given the scarcity of systematized information on the subject, we can highlight:

- The profound imbalances in the availability, composition, and distribution of the workforce; low number of health professionals per inhabitant and concentration of the workforce in large urban centers;

- The unequal presence of technical workers in different countries, with implications for the migration of workers from the Americas and Africa to the central countries;

- The precariousness of work, resulting in the need for workers, especially those in the public sector, to seek a second job; and

- The scarce investments in initial training, technical and professional qualification of these workers.

Primary Health Care 40 years after the Alma-Ata Conference

The theme of Primary Health Care (PHC), on the other hand, is strengthened on the world stage, with the Global Conference on Primary Health Care held from October 25 to 26, 2018, in Astana, Kazakhstan. The event marks the 40th anniversary of the International Conference on Primary Health Care, in Alma Ata, also in Kazakhstan, which defined PHC as a strategy for expanding access to national health systems and, consequently, achieving the goals of the Program for the Year 2000 (SPT 2000).

The idea of APS, however, precedes the Alma-Ata Conference itself. His first record was a report formulated by the then British Health Minister, Bertrand Dawson, in 1920, which served as a reference for the structuring of universal health systems after World War II. Already, at that time, the document indicated: the APS as the base and gateway of the system; regionalization, whereby services are organized locally and regionally by distributing themselves from population bases and identifying the health needs of each region; and completeness, by strengthening the inseparability between curative and preventive actions.

However, it was the Alma-Ata Conference that defined the worldwide guidelines for the development of PHC in the countries: health education focused on prevention and protection; distribution of food and appropriate nutrition; water treatment and sanitation; maternal and child health; family planning; immunization; prevention and control of endemic diseases; treatment of common diseases and injuries; supply of essential medicines.

Over time, this set of actions present in the Declaration of Alma-Ata, and which characterizes the APS as system operator and structuring of universal health systems, came to be called integral (or expanded) PHC. The change in nomenclature emerged to strongly oppose the formulations of the World Bank and the Rockefeller Foundation, which sought to disseminate a concept of selective PHC based on programs focused on specific health problems and targeting populations in poverty. In this sense, the so-called integral PHC reaffirms the right to health as a human right, and therefore universal.

A current reading of selective PHC is the Universal Health Coverage (UHC), whose proposal is to expand access to health services; to reduce the financial difficulties of those who use those services and pay out of pocket, and maintain the financial soundness of pension systems. By limiting the conception of the right to health as an expression of access to insurance, the CUS affirms values such as equal opportunities in liberal societies and hides issues fundamental to the realization of the right to health, particularly social injustices. The UHC has a central role in the financial coverage, with accountability of individuals and lack of accountability of the State, regarding the possibility of access to health insurance, which does not guarantee, therefore, access to services according to health needs.

After 40 years, there are still many issues to be discussed around the different conceptions of PHC, as recently shown by the WHO public consultation on the Declaration of Astana, which title and text refer to the UHC. This fact has generated strong criticism from several entities in the health field, among which the Latin American Association of Social Medicine (Alames), which proposed the exclusion of any form or attempt to subsume the PHC to the Universal Health Coverage of the final declaration.

Although the countries have incorporated the Alma-Ata guidelines in different ways in the elaboration of their national health systems, the proportion of health workers, with emphasis on technical workers, inputs, and financing directed to services linked to the first level of health care has been increasing. Among the changes in the structures and functioning of health services in the last 40 years, we can mention:

- Expansion of access to health services with community orientation and construction of a new model of health care;

- Progressive inclusion of the new labor categories specialized in community work and redefinition of practices of many health professions with new specialties (generalist/family and community);

- Relevant changes in some global health indicators such as the reduction of infant and maternal mortality;

- Incorporation of personnel of origin in their own communities to speak of promoters, sanitary agents, community workers working, for the most part, in scenarios of practice coincident with the scopes where the population itself lives; and

- Incorporation of references such as interculturality in professional practices and public policies as a relevant principle for PHC.

Webcasting

- In Portuguese: https://conferenciaweb.rnp.br/webconf/epsjv-fiocruz

- In Spanish: RETS Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100003023734793)