Climate emergencies: there is no time to waste

More than ever, it is essential to talk about environmental issues that deeply affect health and every other aspect of our social lives. Climate emergencies—manifested in extreme heat waves, floods, droughts, and storms—are becoming increasingly frequent. Directly linked to deforestation, the burning of fossil fuels, and many other human activities, these events lead to deaths, physical injuries of varying severity, and psychological stress among populations, as well as worsening the health conditions of the most vulnerable groups.

More than ever, it is essential to talk about environmental issues that deeply affect health and every other aspect of our social lives. Climate emergencies—manifested in extreme heat waves, floods, droughts, and storms—are becoming increasingly frequent. Directly linked to deforestation, the burning of fossil fuels, and many other human activities, these events lead to deaths, physical injuries of varying severity, and psychological stress among populations, as well as worsening the health conditions of the most vulnerable groups.

The topic, which had already been discussed during the RETS-CPLP meeting held in June this year in Lisbon, returned to the agenda at the 2nd Ordinary Meeting of the Ibero-American Network for the Education of Health Technicians (RIETS), held on October 9 and 10 in Rio de Janeiro. In the year of the 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (Conference of the Parties – COP30), to be held in November in Brazil, it is especially timely to address the issue in connection with the training of health technicians.

To this end, RIETS invited two leading experts on the subject — Renata Gracie, from the Institute of Communication and Scientific and Technological Information in Health (ICICT/Fiocruz), and Alexandre Pessoa, from the Joaquim Venâncio Polytechnic School of Health (EPSJV/Fiocruz) — to participate in the seminar “Climate Emergencies and their Impacts on Global Health, National Health Systems, and the Training of Technicians”, the opening event of the Meeting.

Commitment, not despair

Renata Gracie holds a degree in Geography and a master’s and Ph.D. in Public Health. Among many other roles, she serves as Deputy Director of Research at ICICT/Fiocruz, where she also coordinates the Health Information Laboratory. Together with researchers Christovam Barcellos and Diego Xavier, she leads the team of the Climate and Health Observatory, whose mission is to gather and share information, technologies, and knowledge aimed at developing research networks and studies that assess the impacts of environmental and climate changes on the health of the Brazilian population. In 2024, the Observatory celebrated 15 years of activity, continuing work that had already been taking place within Fiocruz.

Renata Gracie holds a degree in Geography and a master’s and Ph.D. in Public Health. Among many other roles, she serves as Deputy Director of Research at ICICT/Fiocruz, where she also coordinates the Health Information Laboratory. Together with researchers Christovam Barcellos and Diego Xavier, she leads the team of the Climate and Health Observatory, whose mission is to gather and share information, technologies, and knowledge aimed at developing research networks and studies that assess the impacts of environmental and climate changes on the health of the Brazilian population. In 2024, the Observatory celebrated 15 years of activity, continuing work that had already been taking place within Fiocruz.

Renata began her presentation by highlighting the close relationship between capitalist production processes and climate change. “This process has advanced with increasingly larger and more concentrated emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) in the Earth’s atmosphere, leading to a rise in the global average temperature beyond natural variation,” she emphasized. “In 2021, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report warned that even if we stopped emitting these gases for ten years, it would no longer be possible to return to the temperatures originally recorded,” Renata explained.

According to her, this warning was very significant, but many countries have ignored it, further shortening the time we have left to act in order to sustain life. She also explained that the climate crisis arises from the increasing interaction of extreme events—heat waves, storms, floods, droughts, and others. “Each extreme event has a diffuse impact on people’s health. When different extreme events interact, their effects multiply across the population, placing a tremendous burden on the health sector—especially in countries and regions where public health policies are limited, including due to financial constraints,” she pointed out.

According to the researcher, the Climate and Health Observatory seeks to assess health conditions across different regions of Brazil, especially in the areas most affected — that is, peripheral territories such as urban favelas, quilombola, Indigenous, and caiçara communities. She explained that, in addition to working on mitigation—reducing the emission of polluting gases—it is also essential to develop adaptation plans, that is, to anticipate actions that allow us to better cope with the effects of climate change.

"In 2024, we reached the 1.5°C threshold — meaning that the Earth’s average temperature is already 1.5°C higher than pre-industrial levels. This significantly increases the risks of more frequent and intense climate events, such as droughts, floods, heat waves, and glacier melt, among others. If we don’t reduce greenhouse gas emissions, this level will continue to rise, and we will have to implement more and more adaptation measures, especially in the territories where technicians must collect data to help us make diagnoses that truly reflect reality and, consequently, design public policies that better meet the needs of different areas and populations,” Renata explained.

"We want people to leave here committed, not desperate," she emphasized, adding: "Because many didn’t believe in climate change, little was done to stop it. Now, with the increase in extreme events, some believe there’s nothing left to be done — but that’s not true. The less we act, the more the temperature will rise, and the more health problems we will face."

Using graphs and schematic charts, she illustrated the continuous rise in global temperatures and the impact of this warming on human health. “We see environmental impacts from extreme events — such as heat waves, floods, and severe droughts — as well as changes in ecosystems and, consequently, loss of biodiversity, rising sea levels, and agricultural losses. All of these have direct effects on society and population health,” she noted.

According to her, climate change is a global phenomenon, while production models are regional — yet the effects are felt locally. “When we think about diffuse impacts, we realize that we can’t focus only on temperature. We must consider many other aspects and the various diseases that are directly and indirectly affected by these events,” she stated.

According to Renata, the role of the Observatory is to use social analysis, surveys, numerous existing databases, and geoprocessing tools to transform vast amounts of data into information that can guide policymakers in developing public policies more closely aligned with the needs of the health system and different populations — and to inform civil society so that everyone remains aware and engaged.

Focusing on the numerous heat waves that occurred in Brazil between 2000 and 2018, she emphasized that the situation has been worsening, especially in the North and Northeast regions, with dramatic consequences in the form of excess deaths due to high temperatures. “We identified more than 48,000 excess deaths during this period. When a heat wave hits, not everyone can go to the beach, as the newspapers often highlight. Some people work in air-conditioned environments, but many work on the streets, on asphalt, without proper equipment and without taking the necessary breaks. In addition, there are health workers who must be out in the field assessing health conditions and who face these heat waves without adequate support,” she said, stressing the need to provide assistance to these workers, as well as to people with lower levels of education and to Black and brown populations, who are always the most affected.

To detect these extreme phenomena in advance, satellite images are used to, for example, assess vegetation moisture and, through analysis, map periods of drought and relate them to graphs of health events. This makes it possible to demonstrate how different climate events — such as droughts and wildfires — affect population health.

To detect these extreme phenomena in advance, satellite images are used to, for example, assess vegetation moisture and, through analysis, map periods of drought and relate them to graphs of health events. This makes it possible to demonstrate how different climate events — such as droughts and wildfires — affect population health.

In the case of heavy rainfall and floods, radar images are used, since satellite images cannot capture the necessary information. “In this way, we were able to delineate the areas that were actually flooded in Rio Grande do Sul in 2024. Because we had already mapped several geographic features — such as schools, hospitals, Indigenous territories, quilombola communities, and favelas — it was possible to produce and disseminate a technical report containing all the relevant data by municipality. Six months after the disaster, however, we realized that many small municipalities — those that most needed the information — unfortunately had not gained access to the report,” Renata lamented. She emphasized that, “Even though we worked hard on communication, we were unable to reach those municipalities, which showed us that we need to expand our communication strategies so that everyone stays informed and can mobilize, not only during the crisis but also in the post-disaster period — the time of rebuilding cities and lives in the affected areas.”

Before concluding her presentation, the researcher also mentioned the example of air pollution and its effects, particularly on respiratory diseases. “In this regard, we have started developing a system that allows us to estimate pollution levels in specific areas, based on heat sources, with about five days’ advance notice,” she explained, inviting everyone to visit the Climate and Health Observatory website and explore the available materials

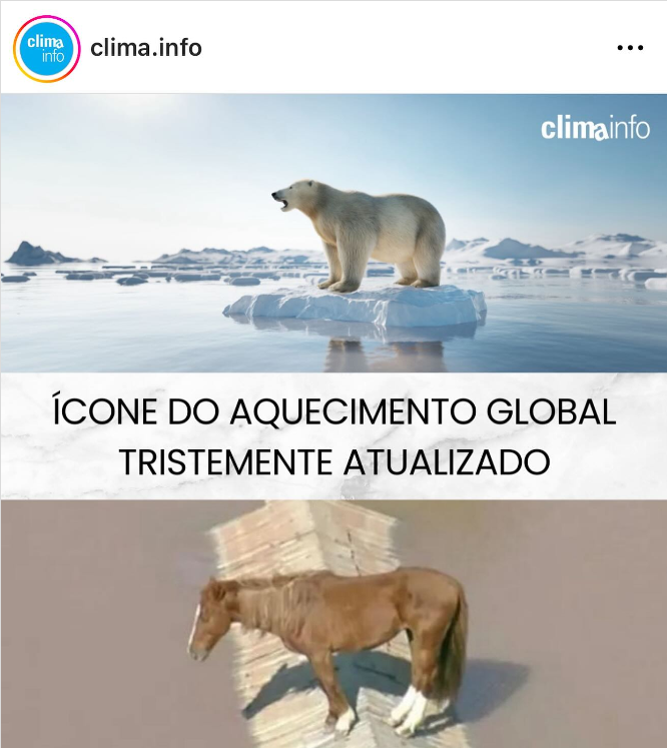

Humanity is walking on thin ice

Among many other roles, Alexandre Pessoa is a sanitary civil engineer, holds a Ph.D. in Tropical Medicine, and a Master’s in Environmental Engineering. He is a professor and researcher at the Laboratory of Professional Education in Health Surveillance (EPSJV/Fiocruz) and represents the School in Fiocruz’s Technical Chamber on Health and Environment. He also coordinates the Water and Sanitation Working Group (GTAS), linked to the Vice-Presidency of Environment, Health Care, and Health Promotion (VPAAPS), and is a member of the Working Group on Pesticides and Health. In addition, Alexandre is part of the Thematic Group on Health and Environment of the Brazilian Association of Collective Health (Abrasco). His areas of work include Environmental Sanitation, Health Surveillance, Agroecology, and Health of Rural, Forest, and Riverine Populations, among others.

Among many other roles, Alexandre Pessoa is a sanitary civil engineer, holds a Ph.D. in Tropical Medicine, and a Master’s in Environmental Engineering. He is a professor and researcher at the Laboratory of Professional Education in Health Surveillance (EPSJV/Fiocruz) and represents the School in Fiocruz’s Technical Chamber on Health and Environment. He also coordinates the Water and Sanitation Working Group (GTAS), linked to the Vice-Presidency of Environment, Health Care, and Health Promotion (VPAAPS), and is a member of the Working Group on Pesticides and Health. In addition, Alexandre is part of the Thematic Group on Health and Environment of the Brazilian Association of Collective Health (Abrasco). His areas of work include Environmental Sanitation, Health Surveillance, Agroecology, and Health of Rural, Forest, and Riverine Populations, among others.

Alexandre began his presentation by noting that the topic of climate emergencies is itself emergent, a term that conveys the idea of new problems that can no longer be postponed. “In this sense, the time variable is just as important as the spatial one,” he said. “Renata and I are part of the Climate and Health Working Group, which brings together several Fiocruz Units — reflecting the fact that the climate emergency affects all fields within the health sector,” he emphasized.

He structured his talk around six key premises, which he considers essential in facing the challenges of this generation. Regarding climate emergencies, he stressed that we cannot speak in the future tense, since these problems are already happening and are causing severe harm to people’s health.

According to the first premise, he recalled that, based on global scientific evidence, the climate emergency represents humanity’s greatest challenge — an unprecedented global ecological crisis. The second premise is that the climate crisis is, above all, a health crisis — the greatest public health challenge of our time. “This second premise brings the issue of the climate crisis directly into our field of work and highlights the enormous effort required from health systems to deal with its consequences,” Alexandre explained. “Climate emergencies bring new challenges, but we also face longstanding ones, especially in the most vulnerable territories and their populations. To me, this is about addressing old problems that are being worsened by the climate emergency. We must study this deeply, or we will not be adequately prepared,” he added.

According to the third premise, the social and environmental impacts of the climate emergency demand concrete actions in technical training and health system strengthening, since there is no time to waste. Deaths can be prevented — which makes adaptive and preventive actions urgent. “Training health technicians is already a concrete action that directly contributes to strengthening health systems. We cannot afford to lose time. During COVID-19, we used the phrase ‘Deaths are preventable,’ and we can still say the same today. Adaptive actions, especially those related to health, must be strengthened,” he stated. “I’m not saying we shouldn’t act on mitigation — we can and must. But it’s important to remember the power of preventive actions in protecting both society and life itself. The challenge is that this requires planning and budgetary organization, even before major climate disasters occur, as many countries have experienced,” he added.

The fourth premise states that the ecological crisis is global, and the response must be global, regional, and local. Therefore, working in networks — through exchanges among educational, research, and health service institutions — is strategic. “Here I want to highlight the potential of networks to share the information necessary for the scientific advances increasingly required in the health field,” Alexandre emphasized.

The fifth premise affirms that climate disasters will occur with greater frequency, intensity, and duration, and thus health systems must be strengthened — with technical training playing a fundamental role, including the development of what he called a “new grammar of the climate emergency.”

Finally, the sixth premise emphasizes that technical education will increasingly require scientific foundations, integrating the natural sciences with the human and social sciences, and uniting the dimensions of work processes, research, and continuing education.

“What we are talking about is that teaching, research, and professional training are increasingly interdependent. We must connect the training of health technicians and all health professionals to these issues. If training institutions and universities fail to do this, they will be producing obsolete professionals — graduates already outdated in the face of the real-world needs,” he warned. “There is, therefore, a new grammar of climate change that must be incorporated into health education. We need to discuss this topic with students while emphasizing the social protection role of their work. Training alone is no longer enough. We must reconnect what should never have been separated — the natural sciences and the social and human sciences,” Alexandre urged. “How long will it be possible to teach health without at least considering the anthropogenic climate emergency and the triad of Economy–Politics–Ecology?” he asked. “The social and environmental determination of health has the potential to provide the necessary critique to overcome the reductionist biomedical model in the face of the climate emergency,” he concluded.

He went on to discuss IPCC reports and Regional Interactive Atlases, highlighting Brazil’s efforts to make these reports more accessible to society and expressing curiosity about how other countries approach this material. “Here, the key findings of the IPCC reports are presented to society on the same day they are released. This is a challenge and reinforces the idea that communication is not just a tool, but a social determinant of health. Communication is an essential component of both education and practice in the territories,” he emphasized. “As Renata said, communication must involve the State, but it also needs to be accessible to populations in real time. Communication helps weave the fabric of life — and it is people, in their communities, who begin rescue efforts during climate disasters. It’s the neighbor, not the State, who starts the fight for life,” Alexandre reiterated, reinforcing the importance of translating scientific reports into the health field, technical training, and public understanding. “We must popularize science,” he concluded.

Alexandre highlighted a statement by António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations since 2017, who said that “humanity is walking on thin ice — and that ice is melting fast.” “This phrase underscores the idea that we have no time to lose and further highlights Brazil’s effort to translate not only the main IPCC report but also several smaller ones, which have an important political function,” he said. According to him, the Summaries for Policymakers allow the scientific community to help guide government decisions. “These accompanying reports are only approved by consensus among countries, which means there is political mediation in their drafting — and therefore, they do not fully express the most severe aspects of reality,” he pointed out. “What impacts are we seeing in Latin America, or in Portugal and Spain?” Alexandre asked.

The researcher also challenged the myth of sustainable development. “This debate is not new. Celso Furtado, one of Brazil’s greatest intellectuals and a key economist in shaping our country’s political thought, was already discussing this in 1973. He spoke of the limits of nature and of what we now know to be irrefutable: the economies of peripheral countries will never develop in the same way as those that make up the core of the capitalist system. If every country were to adopt the production and consumption patterns of the United States, this planet simply could not sustain it,” he explained.

Alexandre also drew attention to a discussion he considers fundamental to understanding climate justice and the geopolitical responsibilities of each country in relation to its actions. He emphasized that discussing this topic in the training of professionals cannot be limited to symptoms, but must address the social determinants of the process. “The biomedical model alone cannot account for this. If we do not intervene in the very conception of the health system, this will not be a deep or meaningful debate,” the speaker urged.

According to the researcher, each country has a different relationship with the processes that cause the climate crisis. In Brazil, for example, he highlighted the destructive power of the agribusiness model, which, he noted, has a greater impact on climate emergencies than the fossil energy system. He pointed out that the Amazon rainforest is undergoing severe stress and a continuous, accelerated process of degradation, even in the face of the climate emergency.

The fact is that all these factors are interconnected. The risks of a pandemic — or syndemic, as COVID-19 was characterized — had already been pointed out in the scientific field for some time, but were ignored by countries. “The 2016 report of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) had already highlighted emerging issues of environmental concern,” he said.

He also presented several examples of EPSJV’s participation in the Mission of REDESCA, the Special Rapporteurship on Economic, Social, Cultural, and Environmental Rights of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) of the Organization of American States (OAS), which took place in Rio Grande do Sul, in May 2024.

He also spoke about the need to educate the population, emphasizing that the mediation of technical professionals is essential and that we must use other “grammars” in health education. “For that, we need dictionaries, right?” he joked, highlighting EPSJV’s vocation for producing dictionaries. “We have the Dictionary of Professional Education in Health, the Dictionary of Education in Rural Areas, and the Dictionary of Agroecology. I consider agroecology to be a very important path for strengthening the community of knowledge that can carry out its own surveillance,” he said. “When you create these communities, you scale up — you save lives,” he assured.