The Region's Health Systems: Back to Normalcy?

The pandemic is no longer an emergency for most countries. America has been one of the hardest hit regions and despite being home to only 8% of the world's population, it had 28.5% of the positive cases and 42.6% of the total global mortality.

Some of the explanations put forward to explain the great epidemiological impact were that the region is the most unequal and unequal and that its health systems were fragile and underfunded.

The pandemic put health at the top of the agendas, and most countries in the region made emergency funds available for the sector because of its impact on all areas of life: economic, social, educational, etc.

Given this prioritization of health on public agendas, the winds of reform began to blow through the region's health systems, and many countries began to talk about the need to make health systems resilient, revitalize the primary care strategy, incorporate the community in health promotion, strengthen human talent, as well as telemedicine opportunities.

The diagnosis was repeated, proposing to overcome fragmentation and segmentation, critical problems in the region's health systems, pointing out the need for continuity of health care, building care networks, and overcoming segmentation among the different subsystems (Social Security, Public, and Private).

Many countries began to talk about the need for an Integrated Health System and to rethink health production modalities, addressing health determinants and risk factors.

Vaccine access has generated declines in lethality. Some countries, such as Argentina and Brazil have advanced in the immunization of their populations with significant percentages of vaccination of their populations, while other countries, especially in the Caribbean region, are still completing vaccination schedules, not even reaching 50% of their population.

The Pandemic, as a global health problem, affects all countries across borders, and as the United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres has repeatedly pointed out, "No one will be safe unless we all are."

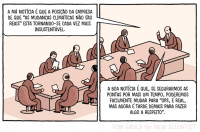

However, we seem to be back to "normal" and the emergency times seem to have passed. The amount of media space devoted to the Pandemic has diminished and the political priority that health issues had on the state and government political agenda has been lost.

In the face of this return to "normalcy," we have also lost the opportunity to discuss and reform our systems and the way we produce health care.

After the peaks of the pandemic waves of morbidity and mortality, the health situation, in general, worsened, worsening non-communicable chronic diseases, and increased indicators of obesity, alcohol, and substance use, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, intrafamily violence, teenage pregnancy, and even increased problems associated with mental health and suicide, among others.

The impact of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine on the region's economy, with slowing growth and inflation, has again generated the need for fiscal austerity and limited budgets, where health is no longer a priority and we have missed the opportunity for health reform.

We did not return to normality, because for two years we lost control of chronic cases, early detection was lost, cases worsened, many of the responses that had been achieved in terms of prevention were lost, and we regressed.