Workshop discusses the strengthening of PHC based on intercultural training

With the theme 'Interculturality and the training of health technicians', the second workshop of the cycle on the training and work of health technicians in the post-Covid world was held on July 12th. The event was opened by Hernán Sepúlveda, Human Resources for Health advisor of the Pan-American Health Organization's Sub-Regional Program for South America (PAHO/WHO-SAM), and also brought together three guests for debate: Herminia Llave Nina (Bolivia), Janete Ismael Mabuie Gove (Mozambique) and Ana Lúcia Pontes (Brazil). The meeting was presented and mediated by Sebastián Tobar, advisor of the Center for International Relations in Health at Fiocruz (Cris/Fiocruz), and Carlos Eduardo Batistella, coordinator of International Cooperation at the Joaquim Venâncio Polytechnic School of Health (EPSJV/Fiocruz).

The workshop cycle is an EPSJV/Fiocruz initiative, in cooperation with the International Network for the Education of Health Technicians (RETS), the Ibero-American Network for the Education of Health Technicians, and the Network of Technical Health Schools of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (RETS-CPLP). Held with the support of SAM and Cris/Fiocruz, it aims to create a privileged space for exchange, reflection, learning, and formulation of proposals for the improvement of institutions and policies for the training of health technicians. The workshops are broadcasted via YouTube, in Portuguese and Spanish, by VideoSaúde Distribuidora of Fiocruz.

Why discuss interculturality in Health?

In his opening speech, Carlos Batistella reinforced that Primary Health Care (PHC) is considered strategic for the population's extended health demands and needs, especially faceing the huge challenges imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic to national health systems.

In his opening speech, Carlos Batistella reinforced that Primary Health Care (PHC) is considered strategic for the population's extended health demands and needs, especially faceing the huge challenges imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic to national health systems.

According to him, it's more than ever necessary to consider the particularities and needs of specific population groups, generally socially and economically vulnerable due to their social or ethnic origin because of colonization processes, structural racism, religious differences, migratory movements, and xenophobia that manifest themselves differently in different countries due to historical and geopolitical contingencies. He said that, "In the health field, there are already several intercultural initiatives that seek the recognition and integration of epistemologies and traditional medical practices of these populations in care programs and policies, but there is still much to do". Pointing out that intercultural work in health requires a deep knowledge of the reality in which it intervenes, as well as knowledge of the needs of the population and culturally diverse groups, respecting their participation in the teaching-learning process.

To conclude, Batistella formulated some important questions for the debate: To what extent has the intercultural dimension been considered in each country's health policies? How to avoid that the users' ethnic and cultural identity represents a barrier to access and opportunity for quality health care in the services? How to reconcile the cultural tensions between the practices of "modern" Western medicine and traditional medicines? How to overcome the perspective of "tolerance" towards the culturally diverse and build an effective intercultural relationship, where the relations of alterity are strengthened, enriched, and mutually transformed? Beyond the language barrier, the disregard of professionals for the beliefs and expectations of their patients for their health-disease process represents an obstacle to the establishment of healthcare actions. What competencies are needed by health personnel for intercultural dialogue? Is it possible to go beyond the educational and communicational dimension of these dialogues, involving community participation in planning and solving the problems encountered? How to avoid the risk of interculturality becoming a discourse of assimilation of social groups, in which traditional practices are revalued, but the analysis and intervention on the historical determinants of their living conditions, are left aside?

Strengthening PHC and changing the paradigm of health education

Continuing the event, Hernán Sepúlveda tried to bring some reflections on the subject, based on what is established in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007). According to Sepúlveda, in Article 24, the UN document states that indigenous peoples have the right to maintain their traditional health practices, as well as to have access, without discrimination, to all existing social and health services. In this sense, according to him, it would be up to governments to make every effort in this regard, including the conservation of medicinal plants, animals and minerals that relate to these cultures. "How can we achieve universal health while respecting these traditions?" he questioned. Then he presented some aspects highlighted in the PAHO/WHO Policy on Ethnicity and Health (2017), in which the Member States agreed to ensure the intercultural approach to health and the equitable treatment of indigenous peoples, people of African descent, Roma, and members of other ethnic groups.

Continuing the event, Hernán Sepúlveda tried to bring some reflections on the subject, based on what is established in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007). According to Sepúlveda, in Article 24, the UN document states that indigenous peoples have the right to maintain their traditional health practices, as well as to have access, without discrimination, to all existing social and health services. In this sense, according to him, it would be up to governments to make every effort in this regard, including the conservation of medicinal plants, animals and minerals that relate to these cultures. "How can we achieve universal health while respecting these traditions?" he questioned. Then he presented some aspects highlighted in the PAHO/WHO Policy on Ethnicity and Health (2017), in which the Member States agreed to ensure the intercultural approach to health and the equitable treatment of indigenous peoples, people of African descent, Roma, and members of other ethnic groups.

According to the PAHO/WHO advisor, in general, in addition to the cultural issues that differentiate them, there are significant geographical issues, since generally, and in most countries, these populations are also far from large centers, living in unserved or under-served areas, where health structures are scarce.

At this point, he cited the Strategy for Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage (WHO, 2014), which states that strengthening the first level of care is paramount since at this level about 80% of people's health problems can be solved. "Unfortunately, in most countries, the biggest concern is still with the secondary and tertiary levels," he lamented, pointing out that increasing the resolutivity of PHC necessarily implies changing the paradigm of health workforce training. "We still train professionals to work in urban centers and with perspectives focused on specialties, and they are hardly willing to work in remote areas. However, if we want to strengthen PHC, we need to train workers who can work with the cultural issues of different populations in the actions of prevention, promotion, and health care; we need to change the curricula and decentralize the training offers, to expand access to the training processes by people from these communities," he emphasized.

About the training and the work of health technicians, especially in the post-pandemic context, Sepúlveda highlighted the role that these workers, who are often the first interlocutors between communities and the health system, had during the pandemic, especially in prevention and immunization actions, and that they will have in the future in the post-pandemic world. "These technicians need to know very well the communities in which they work. Reaching indigenous groups with a syringe requires a lot of intercultural competence," he exemplified.

In conclusion, Sepúlveda reiterated that governments and training institutions must keep in mind that the strengthening of PHC needs to consider the different population groups and that it is necessary to train workers with social awareness. "For all this to occur, however, it is essential that there is a real reform of health systems and that there is, on the part of the government and institutions, the political decision to strengthen PHC," he concluded.

In conclusion, Sepúlveda reiterated that governments and training institutions must keep in mind that the strengthening of PHC needs to consider the different population groups and that it is necessary to train workers with social awareness. "For all this to occur, however, it is essential that there is a real reform of health systems and that there is, on the part of the government and institutions, the political decision to strengthen PHC," he concluded.

Thanking Hernán Sepúlveda for his participation, Sebastián Tobar mentioned the fact that the project of the new Chilean Constitution takes a qualitative leap in this direction, by incorporating the issues of indigenous health and traditional medicine into the care model.

In Bolivia, interculturality from the Constitution to training and work in health

With degrees in Education and Nursing, and a Master's in Public Health, Herminia Llave Nina, professor and head of nursing at the National School of Health (ENS), brought to the workshop the Bolivian experience in the issue of interculturality. The ENS is linked to the Ministry of Health and Sports.

With degrees in Education and Nursing, and a Master's in Public Health, Herminia Llave Nina, professor and head of nursing at the National School of Health (ENS), brought to the workshop the Bolivian experience in the issue of interculturality. The ENS is linked to the Ministry of Health and Sports.

For Herminia, who has a long history of working with indigenous peoples, a major differential of her country is that this issue is expressed in the National Constitution of 2009, which, in Article 3, states that "the Bolivian nation is formed by all Bolivians, by the native peasant nations and indigenous peoples, and by the intercultural and Afro-Bolivian communities that together constitute the Bolivian people," and that "their traditional knowledge and wisdom, traditional medicine, languages, rituals, symbols, and dress are valued, respected, and promoted" (Article 30. II. 9). In addition the Constitution also defines that the health system is unique and includes the traditional medicine of indigenous origin and peasant nations and peoples, with the State having the responsibility to "promote and guarantee the respect, use, research and practice of traditional medicine, rescuing ancestral knowledge and practices based on the thought and values of all indigenous origin and peasant nations and peoples." "Interculturality, therefore, is not a recent issue in Bolivia, we have been working with it for quite some time," she said.

These constitutional premises, according to the professor, mean that the particularities and needs of specific population groups, generally socially and economically vulnerable due to their social or ethnic origin as a result of colonization processes, are recognized by the health system and have grounded the construction of the Intercultural Family Community Health Policy (SAFCI), in 2008, and its implementation strategies. "Based on this Policy, health workers are present in the community, providing access to care, strengthening community participation in decision making, and seeking to articulate what we can call biomedical medicine to traditional knowledge and practices," she explained.

These constitutional premises, according to the professor, mean that the particularities and needs of specific population groups, generally socially and economically vulnerable due to their social or ethnic origin as a result of colonization processes, are recognized by the health system and have grounded the construction of the Intercultural Family Community Health Policy (SAFCI), in 2008, and its implementation strategies. "Based on this Policy, health workers are present in the community, providing access to care, strengthening community participation in decision making, and seeking to articulate what we can call biomedical medicine to traditional knowledge and practices," she explained.

Regarding Higher Education, it is defined in the Constitution as intracultural, intercultural, and plurilingual, and should promote extension and social interaction policies that strengthen scientific, cultural, and linguistic diversity, aiming to build a society with greater equity and social justice, among other things. Higher technical and technological education, in turn, should train professionals with a vocation for service, social commitment, critical and self-critical awareness of the sociocultural reality, the ability to create, apply, and transform science and technology, articulating the knowledge and wisdom of the original peoples with universal knowledge, in order to strengthen the development of the Plurinational State.

All this legal framework has allowed the bolivian National School of Health to implement intercultural aspects to the curricula. She explained that, "today the curricula include, among their areas of knowledge and expertise, the native language, the reality of the Plurinational State (colonialism and decolonization), and traditional medicine which allows its graduates to interact more easily with different populations in the performance of their functions". With that she emphasizes that these areas are developed transversally in the training process.

Herminia concluded her presentation showing the importance that community surveillance, with house-to-house visits, the use of traditional medicine, and health education, among other things, had in the initial control of the Covid-19 epidemic until the health system could be better prepared to provide medicines and vaccines. "At this time, faced with a shortage of human resources, it was necessary to recruit and train students in health careers to allow even the most remote areas to be served, by teams that respect the beliefs and values of these people and know the needs of the different communities," she said. For her, this initial work was fundamental for these populations to later accept immunization and, when necessary, the treatments recommended by biomedical medicine.

In Mozambique, it is necessary to transform the existing policy into practice

To present the experience of Mozambique, the workshop counted with the participation of Janete Ismael Mabuie Gove, who has a degree in Nutrition from the Higher Institute of Health Sciences (ISCISA - Maputo), where she is currently a professor and researcher, and a Master in Food and Nutrition from the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR - Brazil).

To present the experience of Mozambique, the workshop counted with the participation of Janete Ismael Mabuie Gove, who has a degree in Nutrition from the Higher Institute of Health Sciences (ISCISA - Maputo), where she is currently a professor and researcher, and a Master in Food and Nutrition from the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR - Brazil).

Janete started her speech with an overview of Mozambique, a sub-Saharan African country, a secular state, with about 32 million inhabitants (2020), evidenced cultural diversity, and traditional health practices in full force. She then contextualized Traditional Health in the country, recalling that the Policy of Traditional Medicine was approved by the Council of Ministers on March 2, 2004, with several proposals for implementation strategies. "Unfortunately, the Policy is still weakened and the practitioners of traditional medicine are still marginalized, despite there being an Association of Traditional Healers (AMETRAMO) a National Directorate of Traditional Medicine," she lamented.

For Janete it is important we look at traditional medicine based on a different paradigm from the one used by the WHO to define health as the state of full physical, mental and social well-being and not just the absence of disease. "It is necessary to look with other eyes at the issue of ancestral time, the historical aspects of these peoples, their socioeconomic conditions, the ideological changes experienced in the country, and the cultural hegemony.

According to her, in Mozambique Traditional Medicine Practitioners (PMT) are considered a parallel means of health care delivery, with knowledge and skills to educate communities about good health practices, in collaboration with Serviço Nacional de Saúde. "Healers are people who have the gift of communicating with the dead and passing their messages to the living. They have the power of possession, and can treat spiritual illnesses, scare away bad luck, restore luck, and take care of other ailments that have no solution in Western medicine. In addition, people often resort to traditional medicine because of the enormous distances between them and the health units, and only seek the services in case of failure of traditional treatments, often already in critical condition," she explained, adding: "The main question is: how to avoid that the ethnic and cultural identity of users represents a barrier to access and opportunity for quality health care in the services.

According to her, in Mozambique Traditional Medicine Practitioners (PMT) are considered a parallel means of health care delivery, with knowledge and skills to educate communities about good health practices, in collaboration with Serviço Nacional de Saúde. "Healers are people who have the gift of communicating with the dead and passing their messages to the living. They have the power of possession, and can treat spiritual illnesses, scare away bad luck, restore luck, and take care of other ailments that have no solution in Western medicine. In addition, people often resort to traditional medicine because of the enormous distances between them and the health units, and only seek the services in case of failure of traditional treatments, often already in critical condition," she explained, adding: "The main question is: how to avoid that the ethnic and cultural identity of users represents a barrier to access and opportunity for quality health care in the services.

For Janete, first of all it is necessary not to pre-judge traditional health care. That is, it is important that health professionals try to make a historical and social analysis about the forms of health care in each community. Only then will it be possible to sow a good seed of articulation in the preservation of health and life. "Local traditional communities have a social organization with customs, languages, beliefs, and traditions, concerning traditional health care practices recognized by people and should be maintained and valued by all", she said.

Continuing her presentation, she explained that the best way to reconcile the cultural tensions between the practices of "modern" Western medicine and traditional practices involves recognizing existing practices; identifying the folk knowledge that is traditionally used in the prevention, treatment and cure of diseases; creating non-exclusive policies; and conducting research on the medicinal plants used.

The important thing, for her, is to overcome the perspective of "tolerance" towards the culturally diverse and build an effective intercultural relationship, where alterity relations are strengthened, enriched, and mutually transformed. "This depends on effective community involvement, adoption of workable norms or protocols, and not demonization of these practices and knowledge by health workers themselves," she emphasized.

Finally, Janete talked about the competencies needed by health personnel for intercultural dialogue and for the achievement of 'Health for All', recommended in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). "This necessarily goes through the review of training curricula, respect for traditional practices, the provision of health care from a holistic perspective, community participation in planning and solving the problems encountered, encouraging the representativeness of PMTs in their communities, and the integration of traditional and Western or 'modern' health systems, the creation of promoter networks, health education, and the true articulation of knowledge," she pointed out.

In Brazil, the technical training course for Indigenous Health Agents

The Brazilian experience was presented by Ana Lúcia Pontes, MD, PhD in Public Health, who has done outstanding work in indigenous health and the training of Indigenous Health Agents.

The Brazilian experience was presented by Ana Lúcia Pontes, MD, PhD in Public Health, who has done outstanding work in indigenous health and the training of Indigenous Health Agents.

Ana Lúcia, who is currently on staff at the National School of Public Health Sérgio Arouca (Ensp/Fiocruz), began her presentation by bringing some data and a little history of indigenous peoples, who today represent 0.4% of the Brazilian population. "In the 16th century, the estimated population was five million people from more than a thousand peoples. In the 1970s, it was considered that these peoples were going to disappear, due to the high mortality rates or the "assimilation" into the national society. Fortunately, this situation changed and between 2000 and 2010 this population went from about 306,000 to 896,000", she said.

According to her, the indigenous population is distributed in 24 states, 432 municipalities and 505 indigenous lands (12.5% of the national territory), 54% of which are in the northern region of the country (Legal Amazon). There are 305 ethnic groups, speaking 274 languages, and more than 100 records of solitary groups (voluntary isolation). Of the total indigenous population, approximately 64% live in rural areas, while about 36% live in urban centers. "With regard to health and living conditions there are still important inequalities to be overcome," she warned.

Regarding the Constitutional rights, she explained that only in the 1988 Constitution were the Indians' social organization, customs, languages, beliefs and traditions guaranteed, and the demarcation and exclusive use of their territories recognized. The Constitution also ends the idea of State guardianship over Indians. "In 1999, the so-called Arouca Law institutes the Indigenous Health Care Subsystem, in the scope of the Unified Health System (SASI SUS) and defines the organization of care through 34 Special Indigenous Health Districts," he explained, adding: "In 2002 the National Policy for Indigenous Health Care (PNASPI) is instituted, with the objective of ensuring access to comprehensive health care, organized in the form of Special Indigenous Health Districts (DSEI), which must implement primary care actions articulated with the SUS service network, to ensure medium and high complexity assistance. Among the several guidelines established in the PNASPI is the preparation of human resources for the intercultural context", she explained.

She also pointed out that in 1986, the 1st Indigenous Health Protection Conference already defined among its guidelines, the respect and recognition of the indigenous peoples' health notions and practices, and the need to stimulate the training of indigenous people as health professionals, at all levels.

Ana Lucia continued her presentation talking about the Indigenous Health Agents (AIS) in Brazil, whose history dates back to the 1980s, when universities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) carried out projects to train and qualify Indians to develop health actions in the communities. As of 1999, with the Arouca Law, these agents became part of the Multidisciplinary Indigenous Health Teams. "In 1998, there were 1,400 AIS; in 2012 they reached 6,000, and currently there are about 4,000, which, according to some research, have different profiles of action in each region and health district, but which present a strong tendency for the application and distribution of biomedical technologies," she said, pointing out that so far, their work and training have not yet been regulated.

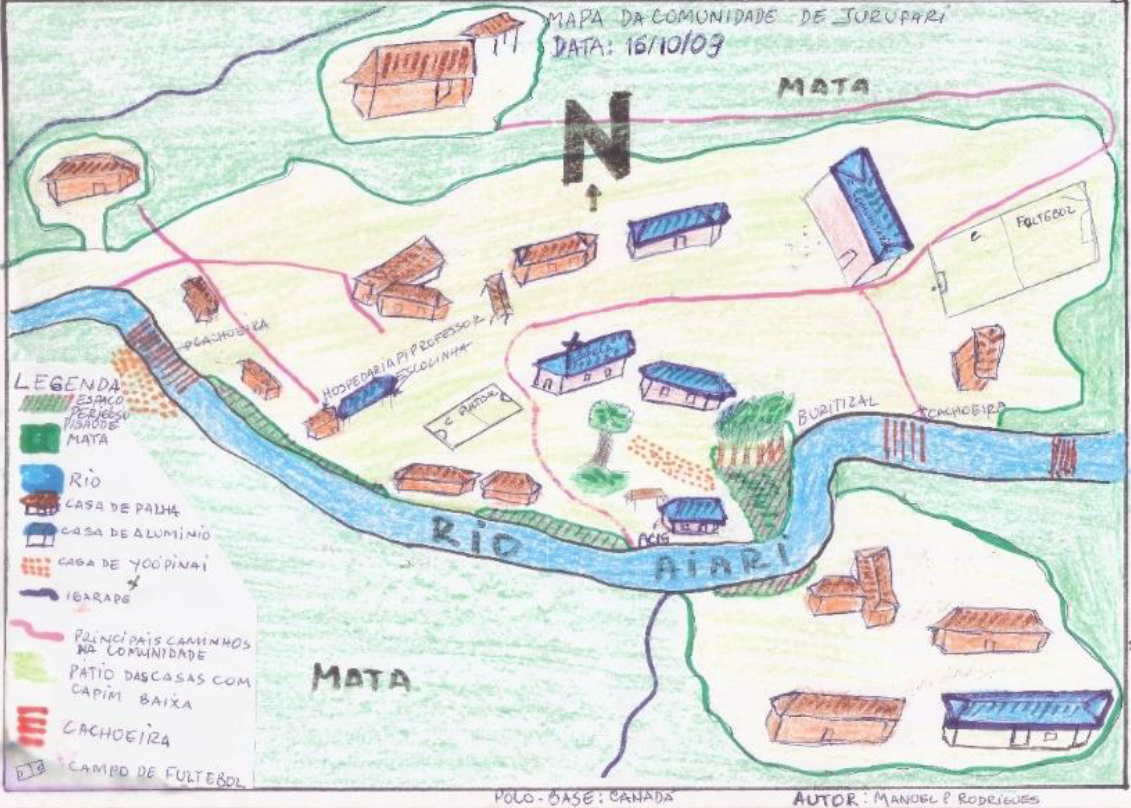

About the Technical Course for Indigenous Community Health Agents (CTACIS), Ana Lúcia reported the experience in the municipalities of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Santa Isabel do Rio Negro and Barcelos (Alto Rio Negro region), where 77% of the population identifies itself as indigenous, and 95% of the population lives in rural areas. In this region live peoples speaking languages from three linguistic trunks: Arawak, Tukano and Maku. The estimated indigenous population totals about 38 thousand people, from 20 peoples, distributed in more than 800 settlements.

The project, according to her, originated in 2007, from a demand by the Federation of Indigenous Organizations and the District Council of Alto Rio Negro, with the aim of providing professional training, appropriate to the local context, and raise the educational level of the agents in service in the region. It is the result of an initial articulation between the Instituto Leônidas e Maria Deane (ILMD/Fiocruz Amazônia) and EPSJV/Fiocruz, and later with other institutions and government agencies.

The course, with a total workload of 1440 hours and developed in face-to-face and semi-presential (professional practice) modality, included three formative stages: elementary school leveling until 2010; high school from 2010 to 2012; and the technical training that started in 2009 and ended in 2015. Of the 198 students who started the course, 139 successfully concluded high school and technical training.

According to Ana Lúcia, the course was developed as a pilot experience that seeks to generate reflections and didactic materials for the qualification of HIAs in other realities, and was based on the following theoretical assumptions:

- Primary Care as a form of organization of the care model;

- Differentiated care as a guideline for the Indigenous Health System;

- Health promotion as an intervention in the determinants and conditioning factors of the health-disease process;

- Health education as a form of empowerment and political strengthening of the subjects;

- Health surveillance as a way to reorganize health practices in the territory;

- Indigenous education: interculturality, bilingualism, dialogical relationship, specificity and difference, cultural diversity; and

- Research and work as educational principles.

Among the didactic and intercultural strategies, Ana Lúcia highlighted: group discussion activities and systematization of knowledge in indigenous language; presentation and debate of the work in the classroom in indigenous language and in Portuguese; observation of productive processes in the community; participation of indigenous narrators and leaders and anthropologists; production of maps of the territories; writing reports and stories; conducting interviews and applying questionnaires; construction of relevant concepts; presentation and debate of videos; production and reading of texts; role-plays; presentations to the community; community task forces; and presentation of the professionals of the Sanitary District and discussion of work routines. "It was a learning experience that provided important tools for the work of these agents in the communities," she added.

Among the didactic and intercultural strategies, Ana Lúcia highlighted: group discussion activities and systematization of knowledge in indigenous language; presentation and debate of the work in the classroom in indigenous language and in Portuguese; observation of productive processes in the community; participation of indigenous narrators and leaders and anthropologists; production of maps of the territories; writing reports and stories; conducting interviews and applying questionnaires; construction of relevant concepts; presentation and debate of videos; production and reading of texts; role-plays; presentations to the community; community task forces; and presentation of the professionals of the Sanitary District and discussion of work routines. "It was a learning experience that provided important tools for the work of these agents in the communities," she added.

She reported some challenges that had to be overcome: the high cost and logistical difficulties in implementing the initiative, the difficulty in finding teachers with the appropriate profile and in producing specific teaching material, the change from a biomedical care model, centered on curativism, to a model focused on PHC and health surveillance, and especially the strengthening of the identity of these agents within the teamwork and the strong resistance of other professionals in the teams to accept the changes in the performance of these workers, some of whom were even fired at the end of the course. "The challenges were many, but there were also advances, for example: the increased commitment of these agents to the training process and to their own communities, the greater articulation between the agents and the indigenous leaders, and the structuring of routines and service protocols, although they have not been effectively incorporated by the services," she reported.

She reported some challenges that had to be overcome: the high cost and logistical difficulties in implementing the initiative, the difficulty in finding teachers with the appropriate profile and in producing specific teaching material, the change from a biomedical care model, centered on curativism, to a model focused on PHC and health surveillance, and especially the strengthening of the identity of these agents within the teamwork and the strong resistance of other professionals in the teams to accept the changes in the performance of these workers, some of whom were even fired at the end of the course. "The challenges were many, but there were also advances, for example: the increased commitment of these agents to the training process and to their own communities, the greater articulation between the agents and the indigenous leaders, and the structuring of routines and service protocols, although they have not been effectively incorporated by the services," she reported.

In closing, she talked about the book 'Differentiated care: the technical training of indigenous health agents in the Alto Rio Negro', which describes the experience; about the Health of Indigenous Peoples VHL, which brings together a large collection of technical and academic materials on the subject; and about the teaching materials aimed at the qualification of indigenous agents.

After the presentations there was an opportunity to interact with the audience in an instigating debate about various aspects of the theme, for about 30 minutes.

Videos of the event in full

-

In portuguese: https://youtu.be/8BqEBxkduYo

-

In Spanish: https://youtu.be/ta-UIPMTUHg

Presentations (PDF)

-

Presentation - Janete Mabuie